List at Least One Factor That Contributed to the Stock Market Crash and the Great Depression Era

Dec 06, 2025

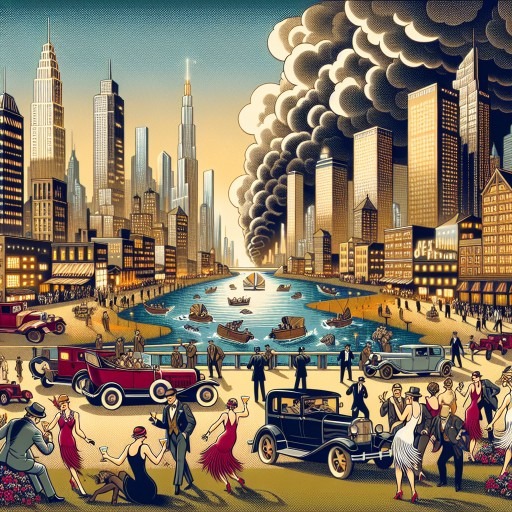

Intro: The Roaring Twenties: A Prelude to the Storm

The 1920s, often called the “Roaring Twenties,” were a period of unprecedented economic growth and prosperity in the United States. However, beneath the glitz and glamour, several underlying factors were silently brewing, setting the stage for the impending stock market crash and the Great Depression. As the wise Niccolò Machiavelli observed nearly 500 years ago, “The promise given was a necessity of the past: the word broken is a necessity of the present.” This astute observation holds when examining the events leading up to the crash.

One of the most significant factors that contributed to the stock market crash and the Great Depression was the excessive speculation in the stock market, fueled by easy credit and speculative fervour. During the 1920s, the stock market experienced a remarkable bull run, with investors from all walks of life pouring their money into stocks, often borrowing heavily. This speculative frenzy was driven by the belief that the market would continue to rise indefinitely, a sentiment echoed by Irving Fisher, a renowned economist of the time, who famously declared just days before the crash, “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.”

Easy Credit and Margin Trading: A System Primed to Detonate

Easy credit was not a side note in the crash. It was the accelerant that turned speculation into a structural threat. By the late 1920s, investors could control enormous positions with only a sliver of cash. Brokers extended loans freely. Banks recycled deposits into market leverage. Margin requirements often sat at ten percent, meaning a single dollar controlled ten. Gains multiplied quickly. Losses multiplied faster.

The numbers tell the story without embellishment. Federal Reserve records show margin debt swelling to more than 8.5 billion dollars by 1929, nearly ten per cent of total market capitalisation. This was not an investment. It was a nationwide leveraged bet built on the assumption that prices could only rise. When the market finally slipped, even slightly, the system snapped. Margin calls forced immediate liquidation. Forced liquidation triggered further declines. The feedback loop became unstoppable.

Jesse Livermore understood the pattern long before the collapse. Human nature repeats. Leverage magnifies its errors. The public chased easy gains, ignored risk, borrowed to amplify fantasies, and refused to consider the downside. When the downside arrived, it arrived with mathematical precision.

The Wisdom of Contrarian Investing

A few understood the danger and acted before the break. Bernard Baruch was one of them. He observed not the headlines, but the psychology. Prices rose faster than earnings. Credit expanded faster than income. Speculation drowned out analysis. Baruch began selling into the strength because the strength was artificial.

His strategy was simple. When the crowd becomes deaf to caution, exit. When valuations detach from reality, they detach from the crowd. He rotated into cash, gold, and high-quality bonds while others doubled their bets. His discipline preserved capital while the market erased fortunes.

Baruch’s actions were not luck. They were the reward for refusing to participate in mass delusion. He recognised that speculation built on borrowed money does not correct itself. It collapses. And when it collapses, only the contrarian standing outside the frenzy escapes the damage.

The Role of Mass Psychology

The stock market crash and the subsequent Great Depression highlight the decisive role that mass psychology plays in financial markets. As the renowned economist John Maynard Keynes noted, “The markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” The collective belief in the market’s invincibility and the fear of missing out on potential gains drove investors to make irrational decisions, disregarding fundamental economic principles.

The concept of herd mentality, where individuals follow the crowd’s actions without independent thought or analysis, was evident during the build-up to the crash. Investors blindly followed the lead of others, assuming that the market’s collective wisdom must be correct. This herd mentality amplified the speculative bubble and ultimately contributed to its bursting.

Technical Analysis and the Early Warnings Ignored

The crash did not arrive without signals. Technical analysis had been flashing red long before panic hit the tape. The most telling sign was the widening fracture between the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Dow Jones Transportation Average. Industrials marched higher through the summer of 1929 while transports rolled over and refused to follow. In Dow Theory, this divergence is not noise. It is structural weakness. When goods stop moving, profits stop growing. When transports break, the economy soon follows.

Volume confirmed the split. Distribution days increased. Rallies thinned. Institutions were quietly exiting while the public continued buying with borrowed money. The charts showed exhaustion even as headlines cheered new highs. The crowd celebrated the price. The tape revealed decay.

The Aftermath and the Framework for Prevention

When the collapse arrived, it erased illusions with surgical speed. A quarter of the workforce lost employment. Industrial production fell by nearly half. Bank failures swept the country, vaporising savings and trust. The crash did not simply end an era of speculation. It exposed the cost of ignoring risk until the system breaks.

Reform followed because the alternative was chaos. The Securities and Exchange Commission was created to enforce transparency and limit manipulation. The Glass-Steagall Act separated commercial deposits from speculative banking, reducing the systemic leverage that had amplified the crisis. These measures did not eliminate greed, but they constrained its ability to detonate the entire financial architecture.

The lesson remains unchanged. Markets always leave footprints before they fall. The tragedy of 1929 was not that the warning signs were subtle. It was that too few bothered to look.

Conclusion: One Factor That Triggered the Crash and Ignited a Global Breakdown

The stock market crash of 1929 did not begin with chaos. It started with belief. Investors convinced themselves that prices could rise without limit, that debt was harmless, and that risk had been permanently defeated. Excessive speculation, fueled by borrowed money, became the engine of a runaway market. By late 1929, more than forty per cent of all stock purchases were made on margin. The market’s foundations were not capital. They were leverage and optimism stacked on unstable ground.

When prices finally cracked, the collapse was violent. Margin calls cascaded through the system. Forced liquidations crushed valuations. Banks, already weakened by thin reserves and poor lending standards, failed in rapid succession. Confidence evaporated. Panic became policy. Within months, the speculative bubble had mutated into a systemic failure.

The damage spread because speculation was only the most visible fault line. Weak regulation allowed banks to gamble with depositor funds. Easy credit inflated demand that could not last. Industrial overproduction created surpluses that no one could afford. Income inequality drained the economy of purchasing power. Each weakness amplified the next until the structure failed under its own contradictions.

The lesson is brutal in its clarity. Markets do not collapse because of one mistake. They collapse when a culture convinces itself that caution is unnecessary. They collapse when mass psychology turns risk into entertainment. They collapse when leverage replaces judgment.

Modern markets carry the same vulnerabilities in different clothing. High-frequency euphoria. Algorithmic contagion. Retail leverage through derivatives. Central bank intervention that encourages risk-taking while punishing restraint. The architecture changes. The psychology does not.

Survival requires more than historical memory. It requires discipline that outlasts mania. It demands a refusal to chase what the crowd worships. It rewards the investor who understands that cycles are inevitable and that patience, not excitement, compounds wealth. Warren Buffett captured this truth without ornament. The market transfers money from the impatient to the patient.

Speculation created the 1929 disaster. Complacency allowed it to spread. The antidote remains unchanged. Think independently. Manage risk before the crowd remembers it exists. Respect history. The investor who internalises these principles does not just avoid destruction. They position themselves to rise when the next wave of collective delusion breaks and clears the field for those who kept their judgment intact.

Words that Resonate: Memorable Articles